By Muna Abdullah, Health System Specialist

UNFPA East and Southern Africa

The cries of newborn twins broke the silence of a small clinic in Malawi, a sound that might not have been heard without the lifesaving skills of Nora, a UNFPA-supported midwife.

Late one night, a young mother arrived after walking for hours, her pregnancy complicated and her life hanging by a thread. Nora, previously trained, equipped with tools, and supported by UNFPA, safely delivered the twins and stabilized the mother. The mother and babies made it through the night – a reminder that timely access to health care and the able hands of a trained midwife can mean a whole world of difference.

From across the world and through generations, pregnancy and childbirth are natural parts of life. However, for many women in East and Southern Africa, they live in a combination of hopeful yet nervous anticipation of childbirth. And for a good reason. Every year, 72,000 women lose their lives from giving birth—an average of 200 deaths every day. Sadly, most of these deaths can be prevented with the right and timely access to quality care.

Reflecting on the strides we made

As we step into a new year, it is an opportune time to reflect on the strides we’ve made and to renew our commitment to building a future where every pregnancy is safe, and every birth is a moment of joy.

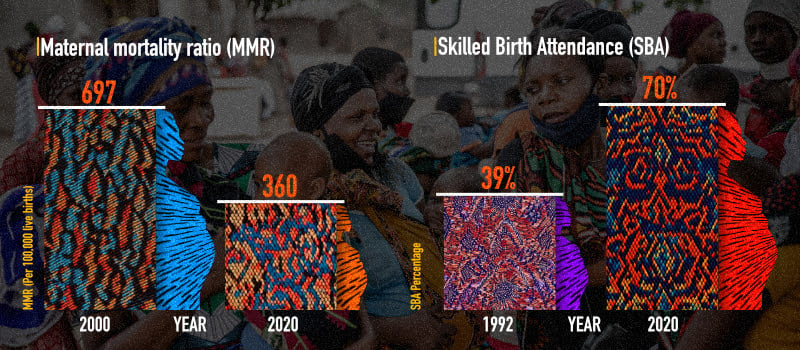

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in the region has dropped by 48 per cent since 2000, with skilled birth attendance rising to 70 per cent.. There has been considerable improvement but the pace is not fast enough to reach the global MMR target of 70 per 100,000 live births set by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Lesotho, Burundi, DRC, Malawi and Zimbabwe recorded high maternal mortality (above 300 per 100,000 live births) despite over 80 per cent of births attended by skilled health workers. Poor quality of care is a significant factor. In addition, young girls experiencing adolescent pregnancies contribute to these high burdens, and in the region, these numbers are twice the global average. Almost 3.5 million adolescent girls give birth in the region annually, most often under risky conditions and without the agency to make informed decisions about their reproductive health.

The situation is further complicated by social and systemic issues. We have cultural norms, economic disparities, and gender inequality that are conducive to essential health services. Vulnerable groups from migrants to people with disabilities and those living in humanitarian crises face even greater barriers. HIV/AIDS also remains a major challenge, contributing to over 10 per cent of maternal deaths in some countries.

There is a silver lining in the horizon. Technology advances are bringing care to previously disconnected areas. Telemedicine and mobile health applications are a few innovations. For example in Tanzania, solar-powered clinics are providing life-saving services in off-grid locations. There are also the possibilities of Artificial Intelligence or AI, and UNFPA is using the technology for midwifery training to equip healthcare workers with critical skills.

For every life saved, an investment is needed. Some countries in the region are below the recommended health expenditure levels. With an increase in funding for maternal and reproductive health services, the prospect of saving countless lives is possible.

With the new year coming and the timeline shortening until we reach the global deadline of the SDGs in 2030, we are fully aware that we still have our work cut out for us. To achieve the targets that have been set in ending preventable maternal deaths, we need thousands of midwives, community health workers, and partners. May Nora, the new mother and the baby twins of Malawi, and millions of others remind us that we have the collective power to save lives.