UNITED NATIONS, New York/Nkhata Bay, Malawi – Five years ago, people living with HIV could receive HIV services and antiretroviral therapy (ARV) at Mzenga Health Centre in Malawi’s Nkhata Bay district only on Tuesdays. As a result, anyone seen entering the clinic on that day of the week was branded as living with HIV and subjected to stigma and discrimination by the community.

“It was so pathetic. At times, people pretended to draw water at the borehole close to the hospital, but their main intention was to see [clinic staff] to get [HIV] drugs,” said Amos Banda, 31, who began receiving ARVs at the clinic in 2008. At times, those charged with picking up ARV treatment were not the people living with HIV themselves, but their children or guardians – and they were then labelled as having the virus. To avoid discrimination, many people living with HIV dropped out of care.

In addition, women in need of family planning services and contraceptives could receive them only on one designated day a week, which meant that many women who did not want their husbands or the community to know they were using contraceptives did not access these services.

But today, thanks to a UNFPA-supported program to integrate sexual and reproductive health and HIV services at 'one-stop' shops, patients are able to visit Mzenga clinic any day of the week to receive maternal, sexual and reproductive health, and HIV services in privacy, from staff trained in all these areas – and in how they overlap.

The case for integrated services

The majority of HIV infections are sexually transmitted or associated with pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, which makes linking the services a natural fit. And the approach doesn’t only reduce stigma - it also improves care.

Because they are now able to provide patients with everything they need during one appointment, as opposed to multiple visits, the clinic is much more efficient. Previously, patients could be made to wait for hours on days when popular services like HIV care were offered; the waiting time has now decreased to the point of becoming manageable. As a result, fewer people are dropping out of care. Plus, the clinic is able to reach people who might have slipped through the cracks in the past. Examples are men who accompany their partners on a maternal health visit, who can now receive HIV and sexually transmitted infection information and testing while they wait.

The program, currently operating in 15 pilot sites in Malawi including Mzenga, is part of a five-year joint UNAIDS/UNFPA initiative to integrate HIV and sexual and reproductive health services in seven African countries – Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe – that rank among the nine countries with the world’s highest rates of HIV.

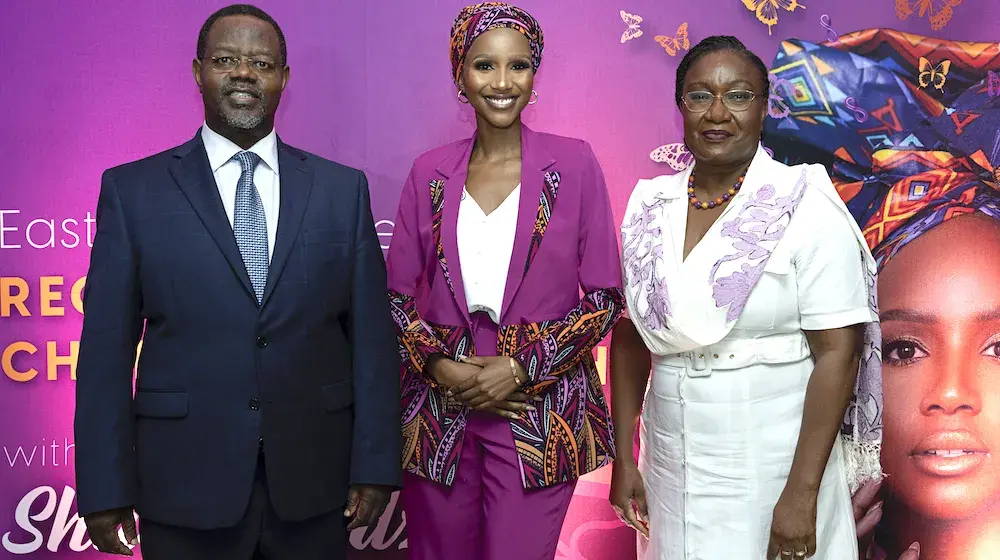

Integrating HIV with sexual and reproductive health and rights makes smart sense. - Dr. Julitta Onabanjo, Regional Director of UNFPA East and Southern Africa.

The pilot programs in all seven countries are showing similarly positive results.

“Integrating HIV with sexual and reproductive health and rights makes smart sense,” said Dr. Julitta Onabanjo, Regional Director of UNFPA East and Southern Africa, during an event on the importance of linking the two, at the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Ending AIDS on 9 June. “And now we have evidence to back integration. There are gains in care efficiency and also increases in patient satisfaction.”

The project hopes to use the evidence of success to scale up integrated services throughout the seven countries, as well as in the East and Southern Africa region, and worldwide.

We young people are having sex, and we shouldn’t have to lie about it. - Violet Lindiwe Banda, a young woman born with HIV

Reaching adolescent girls

Globally, HIV remains the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age. In Malawi, the HIV rate among adults of reproductive age is approximately 11 per cent, although women are much more at risk – claiming a rate of 13 per cent, compared to 8 per cent among men.

Young women and adolescent girls aged 15-24 are among the populations deemed most vulnerable to infection. Across the East and Southern African region, they are up to seven times more likely to be infected with HIV than boys of the same age – and they become infected five to seven years earlier.

Integrated care is proving effective not only in ensuring young women and adolescent girls receive HIV care, but also ensuring they receive other critical services, such as contraception, which are often difficult for adolescent girls to access, especially those living with HIV.

“In Malawi, only a small percentage of youth have access to reproductive health services, and most are not integrated,” said Violet Lindiwe Banda, a young woman born with HIV, at the high-level event. “You cannot distribute condoms in schools. And when we young people ask for contraceptives to avoid unwanted pregnancy, the doctors [at non-integrated clinics] say 'no, it is not good for your health as a person living with HIV'. And we just say, 'okay'. But we young people are having sex, and we shouldn’t have to lie about it.”

– Lucile Scott