ASMARA, Eritrea—Like many young people in Eritrea, Fatma Hamid’s dream was to complete her schooling, do her national service, and get a university degree. But her father had a very different vision for her future, one that he planned in secret.

Ms. Hamid was born in Nafka in 1994, one of four children. Her mother was married off at the age of 14 and by 16, she’d given birth to Fatma, her first child. She wanted a different life for her children and she fought for her children’s right to attend school, in particular her daughter.

My mother didn’t want [ … ] what happened to her repeated with me.

“She didn’t want [ … ] what happened to her repeated with me. She was my biggest supporter, even though they almost broke her down a few times,” Ms. Hamid says. “Even when my parents got divorced and my mother could barely make ends meet by working several jobs, including cleaning our local hospital, offices and other manual labour, she never took me out of school.”

A future on track

She repaid her mother’s sacrifice by working hard and being placed first in her class. Her future seemed on track – yet she was unaware that her father and other family members were planning to force her to marry while still in school.

By the time she approached her final year of school, which she was due to complete at SAWA Training Centre, her mother’s strength had waned. Family members had managed to get her to agree to marry her daughter off, by persuading her that the suitor was a teacher who would see to it that the girl’s education would continue, even after marriage. He was three times her age – and had been her teacher in elementary school.

When the dowry and wedding date were set, Ms. Hamid had no idea of this as the plans were made behind her back. She was upset to discover later that her best friend was in on it. When she confronted her, she was shocked by her friend’s response. “We’re all going to be married off, eventually. This is our fate. Stop fighting it,” Ms. Hamid recalls her saying.

Finding a way out

With her family and best friend conspiring to end her dreams, Ms. Hamid felt her only option was to run away. A plan soon fell into place. As one of the top performing arts students at her school, she was chosen to attend a course run by the National Union of Eritrean Youth and Students (NUEYS) in Xaeda Kristian, not far from Asmara. She jumped at the opportunity and promised to be back in time for her wedding – but she knew she had found her ticket out.

Once the course was completed, Ms. Hamid went into hiding at the home of a compassionate family member in Asmara until the date of the wedding had passed. When the time came, she headed to Gash-Barka to complete her high schooling at SAWA, and qualified for college. She then joined the Eritrea Institute of Technology, known as Mai-Nefhi College, to study for a degree in Applied Biology. Even then the fight to marry her off continued, yet she resisted.

Ms. Hamid completed her degree and was placed at SAWA for two years, where she received an award for teaching excellence. Today, she works at Mai-Nefhi College, on the management team for student affairs. Her work focuses on empowering young women to complete their education, as she did, and to this end she gives seminars, interviews and other engagements.

She plans to continue her education in clinical psychology, with the aim of working with young women to learn about and fight for their rights.

Ms. Hamid harbours no grudge against those who tried to derail her life plans. “It really is a reflection of their own limitations and not of my abilities,” she says.

Child marriage is illegal

In Eritrea, early marriage is prohibited. The legal age for consensual marriage is set at 18 years. The government’s campaign to end this practice, through civil society groups such as the National Union of Eritrean Women (NUEW) and NUEYS, is well documented. Parents who are caught breaking the law face harsh financial penalties and potentially, jail time.

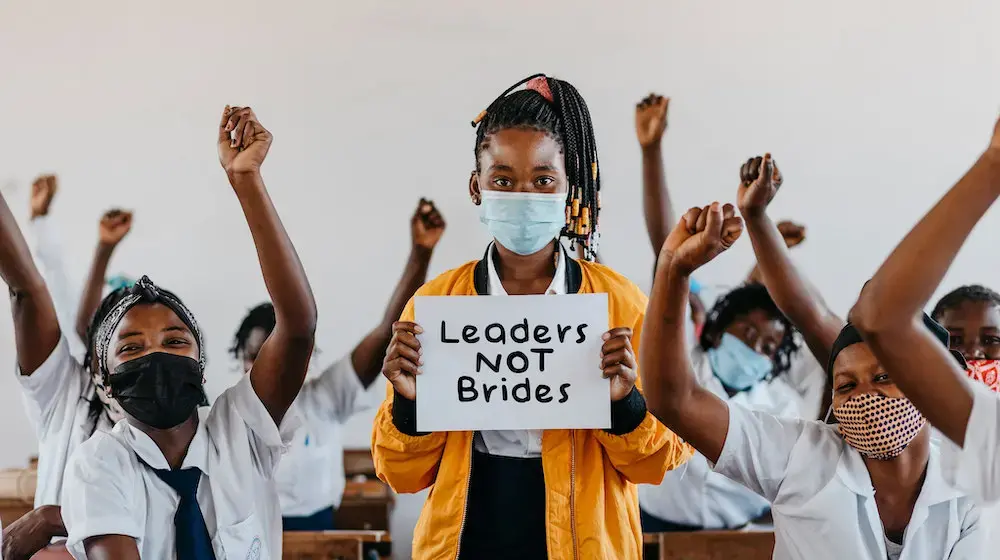

Despite these measures, this and a number of other cultural customs that rob girls of their voice and agency endure. To help counteract them, Ms. Hamid has joined a group of young women that set up a sub-chapter under the guidance of the NUEW. Together, they support the empowerment of girls by tackling issues such as girl’s education, female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage.

If it weren’t for my mother’s faith in me, I probably would have been married by the age of 12.

Now 26 years old and determining her own life course, Fatma Hamid knows that she is one of the lucky ones. “If it weren’t for my mother’s faith in me, I probably would have been married by the age of 12,” she says.

In collaboration with UNICEF, UNFPA supports the government in addressing FGM, early marriage and all forms of harmful traditional practices, funded by the Global Joint Programme on FGM. The Fund works closely with the NUEW, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare to curb the practices using advocacy, community mobilization and awareness campaigns. The Fund supports girls who face these challenges through educational and vocational initiatives. UNFPA also builds the capacity of health-care providers, social workers, legal enforcement bodies, parents, young people and communities.

In 2019, a National Strategic Plan to Ensure Children and Women Rights, Abandon Female Genital Mutilation, Underage Marriage and Other Harmful Traditional Practices 2020 – 2024, entitled Towards Elimination, was developed and is being implemented.