The Guardian. Thursday, 5 April 2012. By Chukwuma Muanya

A UNITED Nations (UN) Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) co-ordinated randomised controlled trial in eight countries has identified a simplified approach to management of the third stage of labour without controlled cord traction (CCT).

The countries include Argentina, Egypt, India, Kenya, the Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, and Uganda. The third stage of labour is the time from the delivery of the infant until delivery of the maternal placenta.

CCT involves traction on the umbilical cord, combined with counter-pressure upwards on the uterine body by a hand placed immediately above the symphysis pubis. CCT is used in conjunction with drugs that speed up the separation process that is syntometrine.

Published in The Lancet, t he study, in which more than 24,000 women participated, showed that omitting controlled cord traction has little effect on the risk of severe bleeding and indicates that effective prevention of Post Partum Haemorrhage (PPH) or severe bleeding after birth could be accomplished with just a uterotonic agent (primarily oxytocin).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PPH is the leading cause of maternal mortality. All women who carry a pregnancy beyond 20 weeks’ gestation are at risk for PPH and its sequelae (a pathological condition resulting from a disease).

Although maternal mortality rates have declined greatly in the developed world, PPH remains a leading cause of maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa.

The WHO has identified PPH as a major cause of severe morbidity and maternal death, particularly in Africa and Asia, where nearly a third of pregnancy-related deaths are associated with haemorrhage (bleeding).

The UN apex health body said most such deaths occur because of insufficient uterine contraction soon after birth. Two management packages for the third stage of labour are commonly used, known as active management and expectant management. In active management, several prophylactic interventions are applied in combination.

A uterotonic is an agent used to induce contraction or greater tonicity of the uterus. Uterotonics are used both to induce labor, and to reduce postpartum hemorrhage. Some uterotonics act as analogues of oxytocin.

Oxytocin is a mammalian hormone that acts primarily as a neuromodulator in the brain.

Oxytocin is best known for its roles in sexual reproduction, in particular during and after childbirth. It is released in large amounts after distension of the cervix and uterus during labour, facilitating birth, and after stimulation of the nipples, facilitating breastfeeding.

The WHO recommends administration of oxytocin soon after delivery of the baby, controlled cord traction, and delayed clamping and cutting of the cord until the health-care worker is ready to apply traction. Uterine massage after placental delivery is included in professional society guidelines. In expectant management, the interventions included in active management are withheld unless needed.

Randomised trials of active versus expectant management have been done in hospital settings and they included early clamping and cutting of the cord in addition to the WHO components. Overall, the risk of PPH was more than 60 per cent lower with active management than with expectant management. The timing of cord clamping does not seem to play a significant part in blood loss. Side effects such as increased blood pressure, nausea, vomiting, and increased placental retention are generally attributed to the use of uterotonic ergot alkaloids.

WHO recommendations published in 2007 advocated the use of the full active management package, while acknowledging the absence of evidence for the effectiveness of some individual components. Estimations of the relative contribution of each of the components could help to determine the most effective way to use the intervention at different levels of health care or by health-care workers with different skills.

Some evidence suggests that the uterotonic component can be effective on its own. However, the contribution of controlled cord traction is largely unknown.

In controlled cord traction the birth attendant pushes the uterine fundus upwards with one hand while the other hand applies continuous traction on the umbilical cord to extract the placenta. Because the procedure requires manual skills, it has been recommended for use by skilled birth attendants only.

However, if traction does not have a meaningful effect on blood loss then it could be omitted and a simplified package focusing mainly on the uterotonic could be recommended. Such a recommendation would have important implications for reducing resources required to train and deploy health-care personnel attending childbirth and could expand access to effective care in places where staff shortages and physical barriers to access remain.

The researchers said the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), WHO, and World Bank-funded findings have important implications for expanding access to effective care and could have a substantial impact on maternal survival in places where access to skilled medical staff is difficult.

The study is entitled “Active management of the third stage of labour with and without controlled cord traction: A randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial.”

The researchers observed that active management of the third stage of labour reduces the risk of PPH, but aimed to assess whether controlled cord traction can be omitted from active management of this stage without increasing the risk of severe haemorrhage.

The researchers did a multi-centre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial in 16 hospitals and two primary health-care centres in Argentina, Egypt, India, Kenya, the Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, and Uganda. Women expecting to deliver singleton babies vaginally (that is, not planned caesarean section) were randomly assigned (in a 1:1 ratio) with a centrally generated allocation sequence, stratified by country, to placental delivery with gravity and maternal effort (simplified package) or controlled cord traction applied immediately after uterine contraction and cord clamping (full package).

After randomisation, allocation could not be concealed from investigators, participants or assessors. Oxytocin 10 IU was administered immediately after birth with cord clamping after one to three minutes. Uterine massage was done after placental delivery according to local policy. The primary (non-inferiority) outcome was blood loss of 1,000mL or more (severe haemorrhage).

The non-inferiority margin for the risk ratio was 1·3. Analysis was by modified intention-to-treat, excluding women who had emergency caesarean sections.

Between 1 June 2009 and 30 October 2010, 12,227 women were randomly assigned to the simplified package group and 12,163 to the full package group. After the exclusion of women who had emergency caesarean sections, 11,861 were in the simplified package group and 11,820 were in the full package group.

The primary outcome of blood loss of 1,000mL or more had a risk ratio of 1·09 (95 per cent CI 0·91—1·31) and the upper 95 per cent CI limit crossed the pre-stated non-inferiority margin. One case of uterine inversion occurred in the full package group. Other adverse events were haemorrhage-related.

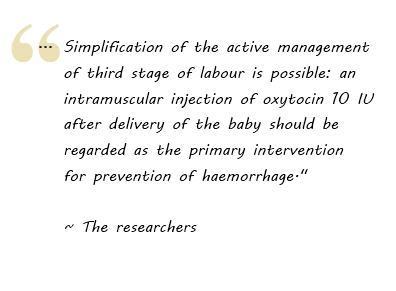

The researchers concluded, “although the hypothesis of non-inferiority was not met, omission of controlled cord traction has very little effect on the risk of severe haemorrhage. Scaling up of haemorrhage prevention programmes for non-hospital settings can safely focus on the use of oxytocin.”

They added, “our findings have several implications for clinical practice. Simplification of the active management of third stage of labour is possible: an intramuscular injection of oxytocin 10 IU after delivery of the baby should be regarded as the primary intervention for prevention of haemorrhage.

“Injections are increasingly being used in settings in which skilled birth attendants are not available but a trained health worker is present. In such settings, oxytocin should be used as the routine uterotonic for prevention of post-partum haemorrhage even if controlled cord traction cannot be implemented. Such a policy could also result in cost savings by eliminating the need for training in cord traction skills.

“In settings in which skilled birth attendants are available, the full package of oxytocin and controlled cord traction should be preferred especially if the shortest possible third-stage duration is desirable. Because a few women will eventually require controlled cord traction with the simplified package and it is the first procedure to be attempted in case of retained placenta, we believe that teaching of controlled cord traction in medical and midwifery curricula should continue.”