LILONGWE, Malawi—Four years ago, the headmaster at Chapita Primary School in Salima considered an enormous challenge that lay ahead of him. Each term, girls would drop out of school due to falling pregnant or marrying early. He wanted to turn around this unsettling trend.

But ensuring that girls stayed in school was no easy task. The proximity of the community to Lake Malawi contributed to students dropping out, says Isaac Zatha, the head teacher.

Every month, I would receive a report of a girl dropping out and by the end of the term, the numbers were significant.

“With money from fishing freely flowing around the communities, the lure of a better life after marriage was too strong to resist for the young girls,” he says. “Every month, I would receive a report of a girl dropping out and by the end of the term, the numbers were significant.”

While boys were also dropping out, the trend was more worrying for girls. In the 2013-2014 school year, four girls fell pregnant and left, followed by five the next year, and then another four.

By age 18, 42 per cent of girls in Malawi are married (2006-2017). By age 18, 35 per cent of girls had already given birth (DHS, 2010).

The adolescent birth rate is high, at 136 births per 1,000 women aged 15 to 19 years. Typically, married girls drop out of school. Just 31 per cent of girls enrol in secondary school (2017). The fertility rate is 4.5 children per woman. More data.

Challenging child marriage

“The community leadership seemed resigned to the fact that it was okay for girls to marry early. Initiation ceremonies were sprouting all over the place even during school time,” says Mr. Zatha.

I knew for this to change, it had to start with the community itself accepting that a girl child’s education was as important as that of boys.

“I knew for this to change, it had to start with the community itself accepting that a girl child’s education was as important as that of boys.”

But to do this, he would need help.

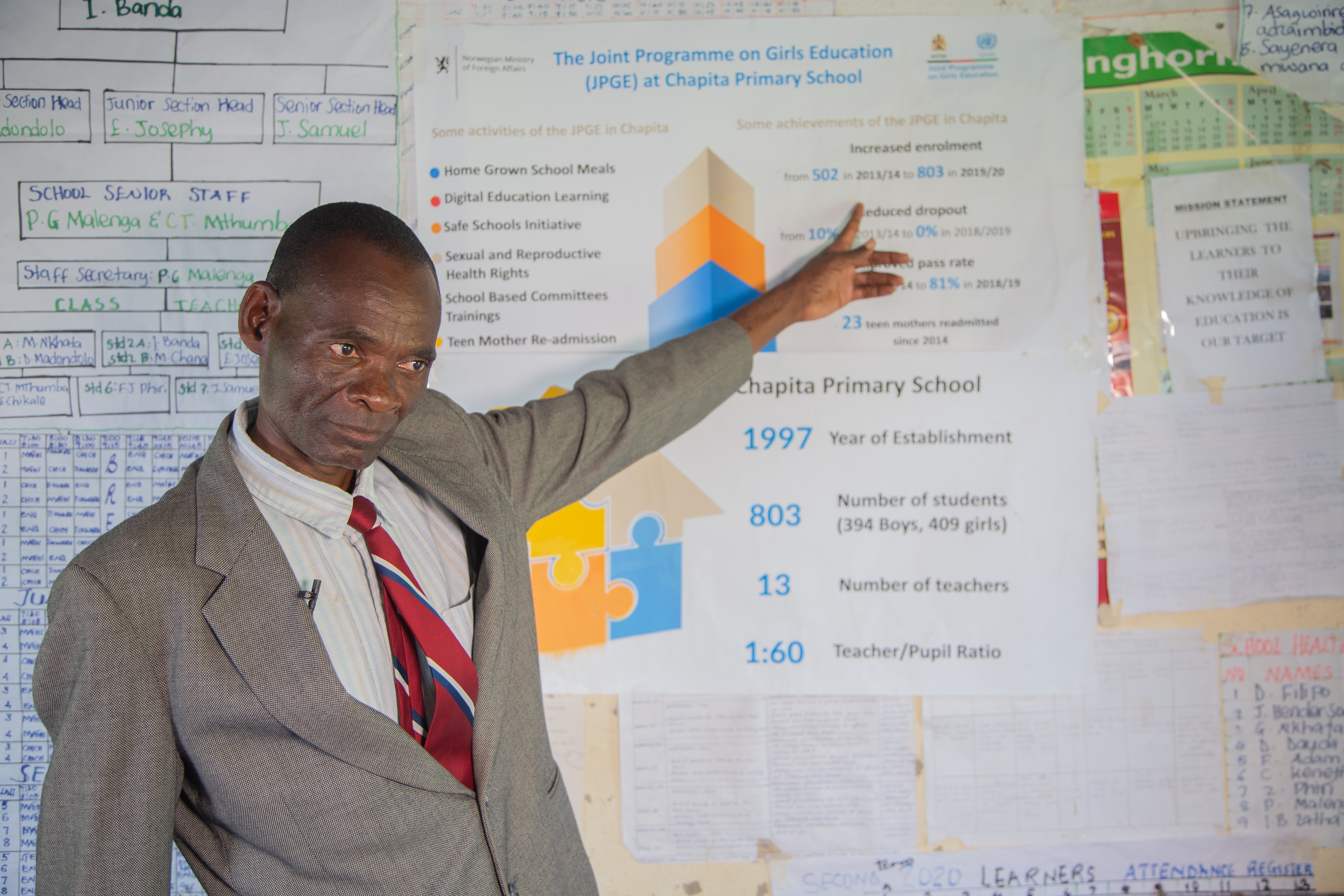

A programme targeting adolescent girls was introduced at the school, with the aim of reducing poverty by improving quality education and basic life skills for girls in and out of school. Known as the Joint Programme of Girls Education (JPGE), it was introduced by the United Nations with funding from the Government of Norway.

“With support from the UN, we have managed to set up different structures in the community and as well as at the school, all with a common goal of making sure that the girl child stays in school,” Mr. Zatha explains.

Implemented jointly by UNFPA, UNICEF and WFP in Dedza, Mangochi and Salima, the programme is already having an impact.

While UNFPA focuses on providing comprehensive sexuality education, the WFP assists with a school feeding programme. “These activities are very important as they are addressing some of the key issues that were leading to girls dropping out of school,” he says.

The programme focuses on girls but also recognizes the importance of involving boys as key to ensuring that girls remain in schools.

Sometimes people question my commitment to work all these years for free, but I can’t express how I feel every time we get a girl back to school.

Mothers’ group to the rescue

A critical component of the programme is the training of mothers’ groups on counselling and on promoting the importance of the girl child’s education. These women track down girls who drop out of school and convince them to return to resume their studies.

But it isn’t smooth sailing, by any means.

“Ours is a difficult job,” says Eunice Mphambo, chairperson for Chapita mothers’ group. “Sometimes we are chased [away] by parents who don’t agree with our work. But we keep on approaching them until they understand that what we are doing is for the good of their child.”

Ms. Mphambo’s education ended early. She has a passion now to encourage girls to do better in life and it motivates her to work hard. For ten years she has been a committed member of the mothers’ group and the results have been rewarding.

“Sometimes people question my commitment to work all these years for free, but I can’t express how I feel every time we get a girl back to school,” she says.

“One of the girls we helped withdraw from early marriage whilst in primary school is now [at] high school. This year, she will write her senior exams. I am hopeful she will do well and inspire more girls in this community to work hard in school,” she adds.

Recently, the mothers’ group managed to convince 15-year-old Laureen Tomasi to return to school after she had dropped out to get married. Laureen eloped with her boyfriend and had been gone for three days. By the time her mother had convinced her to return home, she had lost interest in school.

I thought dropping out of school would give me more time to be with my boyfriend. But the mothers’ group helped me realize that I was making a big mistake.

“I thought dropping out of school would give me more time to be with my boyfriend. But the mothers’ group helped me realize that I was making a big mistake,” says Laureen. “From that day, I committed to go back to school and work hard so that I can help my mother out of poverty.”

Each successful attempt to get a girl who dropped out to return to school is a cause for celebration for her community.

And Mr. Zatha and Chapita Primary School are seeing the fruits of the collaborative efforts. Since the 2017-2018 school year, not one girl has fallen pregnant or dropped out of school.

But this isn’t the only success the school has seen. Their championing of girls’ education has contributed to a rise in girls’ enrolment, from 751 in 2019 to 803 in 2020.

For the community the school serves, this is significant. When a girl stays in school, she delays marriage. A girl who marries later is more likely to work and reinvest her income in her family, which helps lead her family and community out of poverty. Her family is also likely to be more educated and healthier, and hence everyone benefits.

For a school like Chapita to go for two straight years without a girl dropping out or getting pregnant is an achievement that deserves recognition.

Chapita Primary School's phenomenally successful model for keeping girls in school needs to be replicated across the country to ensure that more girls stay in school, says Young Hong, UNFPA Representative for Malawi.

“For a school like Chapita to go for two straight years without a girl dropping out or getting pregnant is an achievement that deserves recognition. As UNFPA, we are ready to talk to our donors and the Government to discuss the possibility of scaling up good practices such as those at Chapita primary school. With enough resources, we can reach out to more districts and ensure that we have many more girls benefitting and going to school,” she says.

For girls like Laureen, the future already looks brighter.

- Joseph Scott