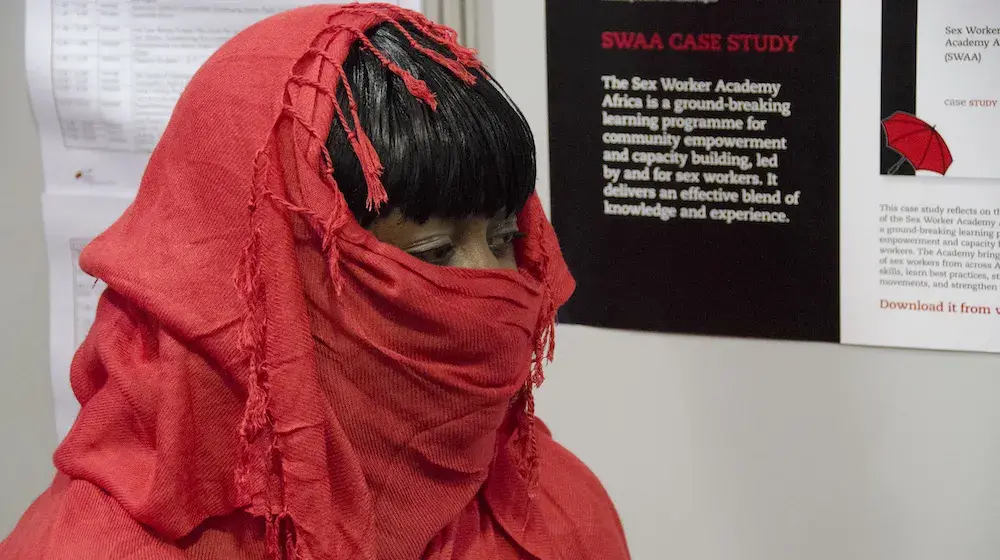

MOMBASA, Kenya and Kampala, Uganda—Each month, Pendo*, a 32-year-old sex worker living with HIV, received antiretroviral medicines (ARVs) and contraceptives at a drop-in centre near her home in Mombasa, Kenya. But under the COVID-19 lockdown, a police roadblock prevented her from accessing the centre.

When ARV treatment is interrupted, those using it can feel ill and they become more infectious. Worried, Pendo called her doctor. He offered to get her a three-months’ supply of ARVs and condoms and to meet her at a nearby church.

“I was very lucky,” said Pendo.

To ignore HIV prevention and sex workers during an emergency is self-defeating. New infections and demands for ARV treatment will burden the health system.

Sex workers are at high risk of acquiring and passing on HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Thus, targeted prevention programmes are critical for public health. In sub-Saharan Africa, 16 countries have an HIV prevalence rate greater than 37 per cent among sex workers.

“To ignore HIV prevention and sex workers during an emergency is self-defeating,” said Innocent Modisaotsile, Regional HIV Adviser for UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency. “New infections and demands for ARV treatment will burden the health system.”

Hard won gains for HIV and AIDS at risk

COVID-19 has brought hardships to sex workers in Africa in particular, in terms of loss of income, police crackdowns, exclusion from social protection schemes, and increased violence from both clients and intimate partners. This threatens hard won gains made to date against HIV and AIDS.

For instance, in the past two decades Kenya’s robust HIV prevention and care programme has reduced HIV prevalence among sex workers significantly. Many of them are now on ARV treatment and they have been empowered to manage their health.

The programme’s mainstay is drop-in centres (DICs) that provide safe spaces, healthcare and peer support. Pendo frequented one of two DICs run by the International Centre for Reproductive Health -Kenya (ICRHK), with UNFPA’s support, near Mombasa.

Under the lockdown, the programme’s strategies were quickly adapted to the curfew and restrictions on mobility and gatherings. Now, tele-counselling is offered for health consultations and treatment support. Clients can get a multi-month prescription of ARVs and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Also available are home deliveries of contraceptives, condoms and lubricants. And for those who are sick, pregnant, HIV-positive and without income, food packages can be delivered.

Business is down. I can’t afford a meal every day.

Violence against sex workers is rife

Pendo’s friend Hamida*, 21, also a sex worker, receives a weekly bag of unga uji (fortified porridge flour). It is this that keeps her going. “Business is down. I can’t afford a meal every day,” she said.

The lockdown has driven the sex trade underground and made it more dangerous for sex workers. Those who serve clients on the streets, in parks or in co-rented flats have experienced sexual violence and forced unsafe sex.

Selling sex in nightclubs, lodgings, bars and brothels is safer, explained Dr. Patricia Owira, ICRHK Project Coordinator. Client registration books, closed circuit television, ejection of violent clients and peer-led responses to sexual violence boost the safety of sex workers.

Yet alleged violence perpetrated by the police against sex workers remains rife. In April, the Global Network of Sex Workers’ Projects and UNAIDS denounced punitive crackdown measures against sex workers, including compulsory COVID-19 testing, arrests and threats to deport migrant sex workers.

In May, the Uganda Key Populations Consortium (UKPC) reported raids, extortion and alleged attacks by the police, including 117 arrests of sex workers in two weeks.

Using innovation to reach sex workers in Uganda

In Uganda, UNFPA scrambled to ensure that HIV services for sex workers remained in operation under the nationwide lockdown. This is critical considering that one in three female sex workers lives with HIV, a prevalence rate five times higher than the national rate. Female sex workers, their clients and their partners contributed 20 per cent of the country’s new HIV infections in 2014.

For five years, a programme run in Uganda by the AIDS Information Centre has delivered a wide range of services to sex workers at clinics, drop-in centres and hot spots. Yet since late March, sex workers’ livelihoods and access to health services have been interrupted by a 7pm to 6am curfew, the ban on movement and public transport, and the closure of bars and nightclubs.

“Sex workers, a key lynchpin in stopping new HIV infections, must not be marginalized by the COVID-19 response,” said Modisaotsile.

With the widespread loss of livelihoods and fewer employment opportunities, transactional sex, sex work and sexual exploitation may increase.

A solution instituted by the AIC was to change their service delivery approach. They used mobile clinics to bring health services not only to sex workers but to entire neighbourhoods. These areas had been mapped by the AIC in 2019 to identify informal settlements with a high number of sex workers and poor young women, whom the pandemic was likely to push into risky sexual choices.

“With the widespread loss of livelihoods and fewer employment opportunities, transactional sex, sex work and sexual exploitation may increase,” warned UNAIDS.

During April and May, the mobile clinics reached more than 68,000 people, including 4,250 female sex workers and vulnerable young women.

Forced into unsafe sex

Fifie*, 25, supports one child and two siblings with sex work. In April, when she had run out of condoms and needed a medical consultation, she walked to Kisenyi Health Centre IV in Kampala twice but the staff were absent due to a lack of public transport.

“Never in my life had I been in such a situation,” said Fifie. With no savings left, few clients and no condoms to protect herself and her clients, she was forced to engage in unsafe sex. “Otherwise my clients would have gone to my competitors,” she explained.

In May, a community activist alerted her about the mobile clinic. Fifie was counselled, tested for HIV (she was negative), treated for an STI, and given a contraceptive injection and a big box of condoms. “This was a golden opportunity. My hope is restored,” she said.

* Names changed to protect privacy.