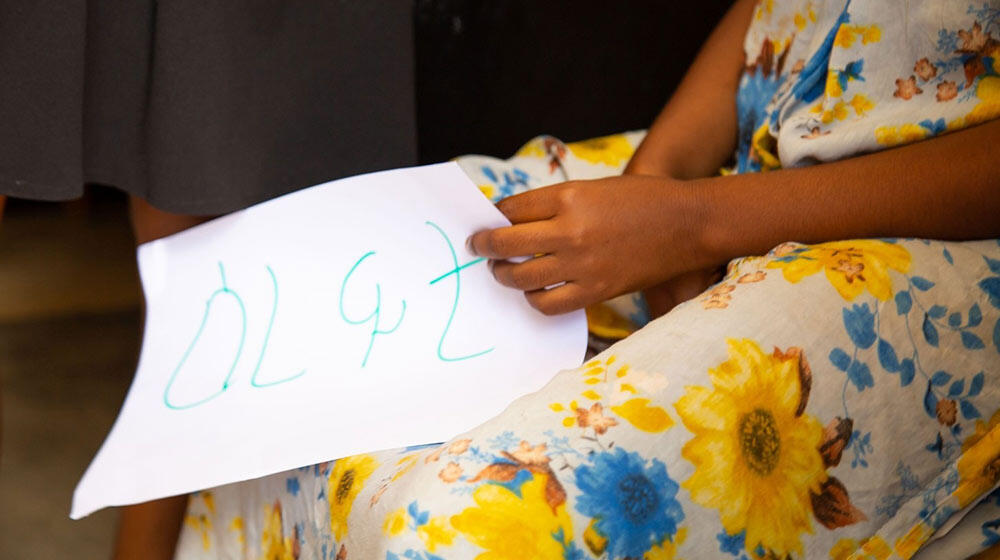

TIGRAY, Ethiopia – “I was running from place to place without food or shelter. I was in fear all the time. There was no safe place for me until I got to the safe house,” 22-year-old Selam* told UNFPA.

Selam was in an extremely delicate physical and psychosocial state when she arrived at the safe house in Tigrinya. She had been displaced by a conflict that continues to rage in parts of the region, and had repeatedly faced harrowing levels of sexual violence.

“Life didn't make any sense to her anymore,” explained the social worker who handled her case.

It is estimated that thousands of women and girls, like Selam, have experienced sexual violence and are in urgent need of supportive services.

I see women and girls arriving here so traumatized and depressed due to prolonged suffering and horrendous violence that they cry and cannot eat for days.

“I see women and girls arriving here so traumatized and depressed due to prolonged suffering, distress and horrendous violence that they cry and cannot eat for days,” added the social worker, whose name is being withheld for security reasons.

UNFPA is providing medical and psychosocial care to survivors, including a safe space where they can heal. These services are crucial for survivors, who need not only immediate responses but also longer-term solutions, including security and stability.

Reported sexual violence is just the tip of the iceberg

Nearly six months of fighting, forced displacement and dire living conditions have created a high-risk environment for women and girls. Gender-based violence has become a daily reality for many in Tigray.

Reports of sexual and gender-based violence are numerous, and they likely represent just a fraction of the real incidence. Gender-based violence is largely unreported even under normal circumstances – with only 23 per cent of survivors ever seeking assistance, according to a 2016 survey.

“Survivors fear seeking care due to social stigma, further retaliation or limited access to service providers,” said Tesfu Alemu, a UNFPA programme officer. “Silence is a widespread coping mechanism, but survivors must know about the benefits of seeking care and that help is available.”

I have never received such dignified care in my life.

This care can make all the difference.

“I didn’t know that there were people who can help or do anything, even that women have rights. I found out when I arrived at the safe house,” said Selam. “I have never received such dignified care in my life.”

“They really change here,” the social worker said of the survivors who are supported at the safe house.

Need to scale up

As the conflict drags on, UNFPA estimates that tens of thousands of people may end up requiring medical services to address sexual and gender-based violence in Tigray and the neighbouring conflict-affected regions of Amhara and Afar. Yet only 29 per cent of health facilities in Tigray are partially available to provide clinical management of rape; none are fully available.

And while an estimated one in five people affected by conflict experience a mental health condition, according to World Health Organization researchers, the availability of mental health and psychosocial support is far below the current needs.

“The long-standing impact of the crisis in Tigray on women and girls, and the disruption of systems and services they normally rely on, underscores the acute needs for comprehensive assistance for sexual and gender-based violence, including mental and psychosocial first aid,” said Diana Garde, UNFPA’s humanitarian coordinator.

UNFPA is currently scaling up its support to safe houses, which not only provide clinical management of rape and psychosocial counselling, but also connect women to other sexual and reproductive health services. The Fund is expanding the availability of one-stop centres – which provide a wide range of care – and women’s and girls’ safe spaces across the conflict-affected regions. The agency is also providing medical supplies and equipment to restore health system services.

UNFPA currently requires at least $12 million to provide this life-saving support, of which less than 40 per cent has been funded.

As for Selam, she says she is determined to move forward. She has found renewed hope and purpose, she said, in part because of the inner strength she summoned while at the safe house.

“When I leave this house, I would like to train and help other women like me in my community,” she said.

* Names and identifying details have been changed or omitted for their privacy and protection.