HA MOEKETSANE, Mokhotlong district, Lesotho—For Regina Mokoena, a village health worker at Ha Moeketsane, family planning becomes even more of an imperative in times of drought. Especially for women. And the new self-injection contraception method, Sayana Press, is making important inroads in rural areas where clinics are hard to reach.

In these difficult times, it is not easy to look for a job or to get employed when you have many children, especially here in the village.

© UNFPA Lesotho/Violet Maraisane

“In these difficult times, it is not easy to look for a job or to get employed when you have many children, especially here in the village. We mostly survive on farming and Food for Work. Besides, educating children is also very demanding,” she says.

Increasingly unpredictable weather conditions caused by climate change are resulting in drought in the small, landlocked nation. During last summer’s cropping season, the district of Mokhotlong was one of the hardest hit by the severe drought. Many farmers lost a significant proportion of their livestock, their main livelihood. The main source of income for the Basotho people is agriculture and livestock farming.

When livelihoods are lost, economic survival becomes harder. Money for food, health, education and other basic necessities is reduced for families. The more mouths there are to feed, bodies to clothe, and minds to educate, the less money there is available to spend on each one of them.

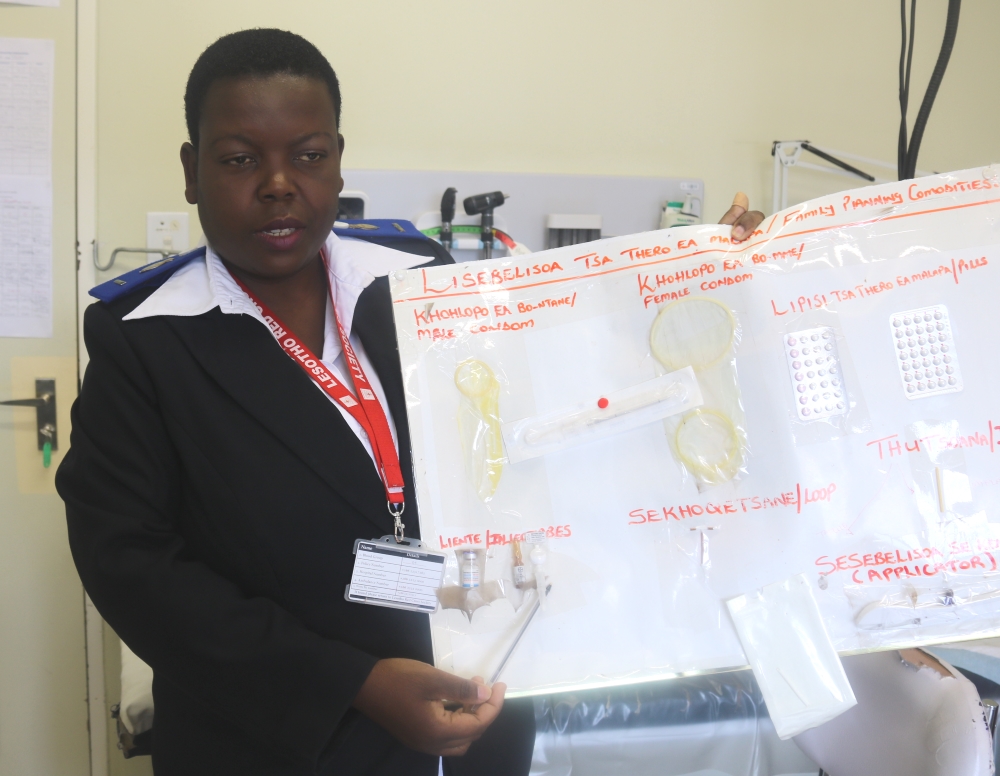

Ms. Mokoena is one of the village health workers who has been trained by the Ministry of Health, with the support of UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund, on administering the new self-injection family planning method, subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, or Sayana Press.

Lesotho commits to reducing unmet need for family planning

Press, on a chart. © UNFPA Lesotho/Violet Maraisane

Mokhotlong district has one of the highest rates of unmet need for family planning in the country, at 25 per cent, compared to 18 per cent nationally. It also has the lowest contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR), at 48 per cent.

This scenario leads to high rates of unplanned pregnancy, school drop-out, child marriage, teenage pregnancy, unsafe abortion and maternal deaths. The fertility rate for Lesotho is 3.2 children per woman; however, in Mokhotlong district the rate is the highest, at 4.4 children per woman. Mokhotlong also has the second highest teenage pregnancy rate, at 24 per cent.

The Government of the Kingdom of Lesotho recognizes universal access to sexual and reproductive health and rights as one of the cornerstones of population and development, and as a key target of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The government has committed to reducing unmet need for family planning from 18 per cent to 11 per cent by 2023, and to increasing CPR from 60 per cent to 80 per cent by 2023.

The primary reason for the hospitalization of women and girls in Lesotho is unsafe abortion, according to the 2019 Annual Joint Review. The use of family planning reduces rates of unplanned pregnancy. Lesotho has committed to getting an additional 61,776 women of reproductive age on long-term contraception methods by 2023; up from the current figure of 29,094.

Village health workers boost access to family planning

Ms. Mokoena sings the praises of this new contraceptive for reducing the number of clinic visits required. Because women using Sayana Press are able to self-inject it in the comfort of their own homes, this means they no longer need to visit a health facility regularly – a saving grace for those who live far from their nearest clinic.

Ms. Mokoena’s job as a village health worker also involves ensuring that pregnant women attend antenatal clinics and that those who are ill adhere to their medication regimes. Following the training she received on Sayana Press, she and other village health workers have been holding public gatherings to inform people on the use and disposal of the new contraceptive.

I like the new contraceptive as it will help me space my children.

Thato* is one of those who is considering using it. “I like the new contraceptive as it will help me space my children,” she says. “I am currently afraid to inject myself though. But I guess I will have to overcome my fear to avoid regularly walking for close to an hour to get to the clinic.”

The first cohort of village health workers was trained on the self-injection method in September 2019, according to ‘Manthati Sekoati, Nurse-in-Charge at Mapholaneng Clinic in Mokhotlong. Sayana Press is attracting new users who are requesting it at the clinic.

To help women overcome their fear of injecting themselves, they are advised to visit a clinic where they can be assisted with this by the health professionals, she says.

When self-injection family planning is a blessing

This new family planning method helps reduce congestion at the clinic. If more women choose to inject themselves at home four times a year, they would not need to visit the clinic as regularly for family planning services, Ms. Sekoati says.

It empowers women to take control of their fertility, when their husbands’ desire for large families and societal expectations of high fertility restrict them in this respect. It also helps reduce stigma and discrimination, particularly among young people who are often embarrassed to be seen at a clinic, she believes.

And with continued education on this form of contraceptive, those who are afraid to inject themselves will have a better understanding of the process, enabling them to overcome their fear.

UNFPA is also supporting drought-affected communities, especially women and girls, by responding to gender-based violence, with funding from the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF).

- Violet Maraisane

* Not her real name.