AWASH, Ethiopia – Twenty-four-year-old Hawa Buha was among the first in her conservative pastoralist community to defy the tradition of female genital mutilation (FGM). Here, in the northern Afar Region, many believe that “an uncircumcised girl is one who is waiting for her day of circumcision, or one who has already passed away.” But Ms. Hawa had other ideas.

The Afar Region has Ethiopia’s second highest rate of FGM. There, infibulation – the severest form of FGM – is commonly practiced. It involves the removal of the clitoris, labia minora and labia majora, followed by sealing the wound. The procedure leaves many girls with severe pain, trauma and complications.

Ms. Hawa was in elementary school when a project, started by CARE Ethiopia, began raising awareness of the harm caused by FGM. The message resonated with her, and she declared to her parents that she would not be circumcised.

Her parents were eventually convinced, and she was spared what her elder sisters had endured. But the years following this decision were very difficult.

Ms. Hawa was ridiculed for challenging a long-cherished tradition. “People were saying that I would die as a witch as no one would marry an uncircumcised girl,” she remembered.

A harbinger of change

As the years passed, Ms. Hawa began to feel less alone in her decision. More and more girls began adopting her position.

In 2000, religious leaders in Afar launched a campaign to abandon FGM. Imams worked tirelessly to explain to leaders and community members that the practice had no basis in Islam. And in 2006, the Afar government passed a regulation reaffirming the position of the Penal Code of Ethiopia (ratified in 2005), which criminalizes the practice.

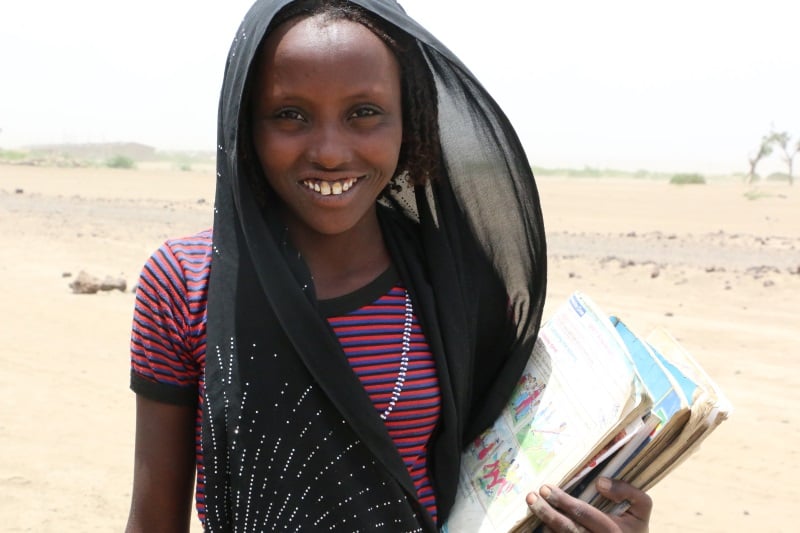

A schoolgirl in Doho locality, where Ms. Hawa lives and where the Joint Programme is being implemented. Doho has been chosen as a model locality. © UNFPA Ethiopia/Abraham Gelaw

A schoolgirl in Doho locality, where Ms. Hawa lives and where the Joint Programme is being implemented. Doho has been chosen as a model locality. © UNFPA Ethiopia/Abraham Gelaw - See more at: http://www.unfpa.org/news/young-pioneer-ethiopia-defies-fgm-finds-love#…

A schoolgirl in Doho locality, where Ms. Hawa lives and where the Joint Programme is being implemented. Doho has been chosen as a model locality. © UNFPA Ethiopia/Abraham Gelaw - See more at: http://www.unfpa.org/news/young-pioneer-ethiopia-defies-fgm-finds-love#…

A schoolgirl in Doho locality, where Ms. Hawa lives and where the Joint Programme is being implemented. Doho has been chosen as a model locality. © UNFPA Ethiopia/Abraham Gelaw - See more at: http://www.unfpa.org/news/young-pioneer-ethiopia-defies-fgm-finds-love#…

|

But the work was not yet done. Many communities within the region continued to practice FGM.

In 2008, the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting began working in Afar. With a core group of reformers, the Programme helped mobilize further support for ending the practice.

At community conversations held every two weeks, community members themselves began to challenge entrenched ideas about FGM. Committees were set up at the kebele (sub-district) and village levels to monitor progress. These committees comprised local leaders, ex-circumcisers, local judges, village elders and religious leaders.

By 2013, all of the six Afar districts covered by the Programme had publicly declared abandonment of FGM. Some 7000 girls, including Ms. Hawa, were spared circumcision during this period – an unprecedented trend.

Once thought unmarriageable, now caught between two men

But Ms. Hawa was not finished being a trailblazer. She wanted to forgo another tradition, known as ‘Absuma’, which requires a girl to marry her eldest first cousin. Instead, she wanted to marry Enehaba Seid, a long-time friend and schoolmate.

When Mr. Enehaba asked for Ms. Hawa’s hand in marriage, an uproar ensued. The cousin who had expected to marry her gathered his relatives together and threatened Mr. Enehaba. Once considered unmarriageable, Ms. Hawa found herself caught between two men.

Following negotiations involving clan leaders, the matter was finally resolved and Ms. Hawa was able to marry Mr. Enehaba.

“We are the pioneers in our locality, and many young people have followed us,” he explained. “In the past, no one wanted to touch an uncircumcised girl; now, young men are fighting over these girls.”

They now have two children, a girl and a boy. And their family continues to serve as a model to their community. Despite her responsibilities as a wife and mother, Ms. Hawa has stayed in school. She will soon take her high school exit exams, and dreams of going on to college.

By Abraham Gelaw

Story from the 2014 Annual Report of the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting.