Blog by Lydia Zigomo, UNFPA Regional Director

A poignant story about a woman from Malawi this week resonates deeply with me. At the age of 40, Mary went for cervical cancer screening and tested positive. Because the cancer had spread to her uterus, her only option was a hysterectomy. But Mary had been trying for 10 years to start a family. Sadly, she declined the operation and passed away from the disease in November last year.

Her tragic death is all too common in Malawi, a country with one of the highest mortality rates due to cervical cancer, and in other parts of the region. It is a narrative that we must change – because cervical cancer is one of the preventable and treatable forms of cancer.

Cervical cancer is most often caused by certain strains of the human papillomavirus virus (HPV). Although every girl or woman who is sexually active will become infected with HPV, most strains are benign and will not harm people with healthy immune systems.

It can take 10 to 20 years for the HPV infection to progress to cervical cancer, less time if the immunity of the woman is compromised, as in HIV infection. Hence, periodic screening programmes have great importance in the prevention of cervical cancer. With the advancement of medical technology, cervical cancer screening has the potential to be easily accessible. Nowadays, self-care interventions offer women the ability to take a sample themselves for testing for HPV infection.

Even if the HPV infection progresses to cervical cancer, it can be treated if the cancerous cells are detected early and managed well. Yet, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women globally. In 2020, about 604,000 new cases were detected and 342,000 women lost their lives. About 90 per cent of those new cases and deaths occurred in low and middle-income countries.

Despite recent advances, the rate of cervical cancer is on the increase in some sub-Saharan African countries – 19 of the 20 countries with the highest caseloads are in East and Southern Africa. I have just been visiting South Sudan and in my meetings with one of the youngest Ministers of Health I have met on the continent, who is also female, together with her team, they shared with me their concern about a rise in cancers, especially cervical cancer among women, including young childbearing women, and the need to integrate this into the package of services for reproductive health screening and treatment they offer.

Why does this trend persist? It boils down to inadequate screening of women and girls, late diagnosis, limited access to timely and quality treatment, and high HIV prevalence.

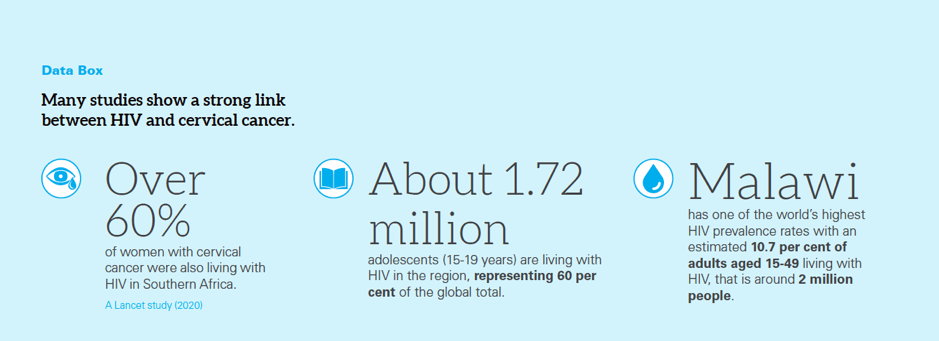

Studies show a strong link between HIV and cervical cancer. Women living with HIV are six times more likely to develop cervical cancer than women not living with HIV, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

In a crucial step forward, the WHO World Health Assembly adopted a global strategy highlighting cervical cancer as a public health concern in 2020, which recommends a comprehensive response to cervical cancer.

As UNFPA, we know that cervical cancer prevention and treatment programmes are essential in East and Southern Africa due to high HIV prevalence rates. About 1.7 million adolescents aged 15 to 19 years are living with HIV. Adolescent girls and young women aged 15 to 24 years make up 26 per cent of all new HIV infections in the region.

Malawi has one of the world’s highest incidences of cervical cancer, and the highest number of deaths – 52 women per 100,000 women lose their lives every year. This rate is double that of East and Southern Africa, and seven times higher than the global rate. Malawi also has one of the world’s highest HIV prevalence rates – an estimated 10.7 per cent of adults aged 15 to 49 live with HIV.

Many women in the region face several barriers to screening and treatment of cervical cancer. Their male partners are often reluctant to allow screening for cervical cancer, particularly if the health worker is male. Rumours abound that the instruments used could cause infertility. And health workers can be impatient, or due to a high workload, ask women to return on another day for screening. To improve screening – and survival – rates, fears and attitudes like these need to be addressed. Where there is a supportive health system and HPV tests are available, HPV self-sampling helps to improve cervical cancer screening coverage. Women may feel more comfortable taking their own samples, rather than going to see a health worker for cervical cancer screening.

In Malawi, an integrated programme offers a package of same-day services for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). Four UN agencies, including UNFPA, in partnership with the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, launched this programme in 2018. Through the 2gether 4 SRHR programme, women and girls receive cervical cancer screening at the same time as family planning, HIV testing, and gender-based violence services, as needed.

The programme also opened up access to remote regions. Girls and women aged 15 to 49 received cervical cancer screening in rural communities in the districts of Mangochi, Nkhatabay and Mulanje in Malawi. Potential barriers to screening were overcome by involving high-level government officials and forming an advisory committee of women living with HIV. Additionally, traditional and religious leaders were brought on board.

The results speak for themselves. The number of women and girls screened for cervical cancer increased from 2000 in 2019, to more than 9900 in 2020, and close to 11,000 in 2021, of which more than 2000 tested positive. They received treatment at the health facility or referrals to the district hospital.

Bringing cervical cancer services to remote areas is critical for reaching women who live far from health facilities. They do not have to leave their children, farms, or small businesses unattended, which makes them lose vital family income. And undoubtedly, winning the influence of traditional leaders helped dispel myths and fears, as did the involvement of HIV support groups.

In a region rocked by HIV and cervical cancer, the positive results of this initiative are important and timely. It gives us hope that there need be no more tragic stories of lives lost unnecessarily – like Mary’s.